Impacts of processor stress and consolidation

on harvesters and communities

Ocean Strategies Senior Consultant Hannah Heimbuch delivers her first installment to her family’s personal story amid Alaska’s fish processing challenges. Be sure to read her Close-Up on Closures, Part II published mid-July 2024 and stay tuned for more as her summer fishing season unfolds.

We talk a lot about access challenges in the fish world. Quota consolidation and permits leaving communities. Reallocation between sectors, grounds pre-emption by other industries, natural disasters and climate crises.

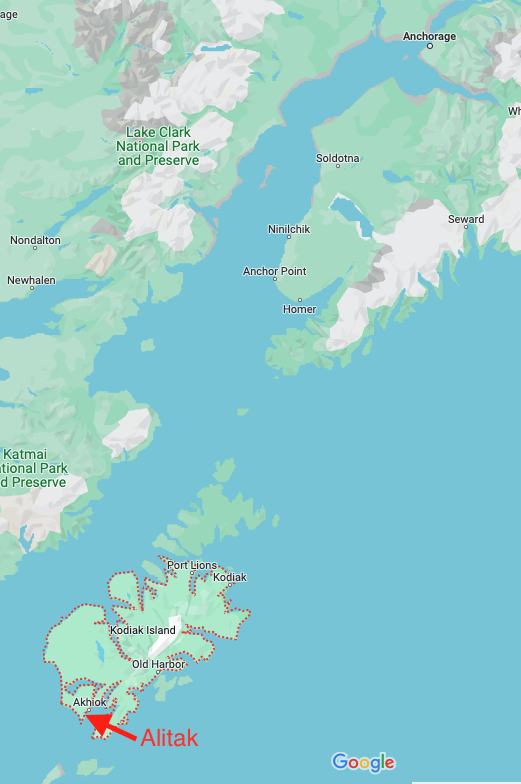

And then there are the market-based disasters, like the one my remote Alaska fishery — and others like it — are experiencing right now. Just three months out from salmon season, my fleet is ready and able to fish, but we’ve lost access to the marketplace. The only fish buyer for Alitak (a remote island bay in the Gulf of Alaska) dropped our setnet fleet from its summer operations. For the first time in more than a century, our area has no buyer. And like so many similar harvesters across the state, the rest of our logistics crumble without them.

It’s just the latest in a swath of industry shake-ups across Alaska, the kind that happens every couple of decades. The trend started with Trident Seafoods’ December announcement that they would be selling processing facilities in Kodiak, False Pass, Petersburg, and Ketchikan — more than a third of their Alaskan processing facilities. Trident Seafoods is currently the nation’s largest seafood company. But this was followed by Peter Pan Seafoods’ shutting down its King Cove facility during pollock A-season and then the loss of its Sand Point plant to fire. And more recently an announcement from OBI to shutter its Larsen Bay plant for the summer salmon season. (See this recent Ocean Strategies write up for more Alaska and national context.)

Three months might seem like a good amount of time for Alitak fishermen to pivot to a new buyer, but not necessarily in a place with Alaska’s logistical hurdles. Alitak is 120 nautical miles from Kodiak town, the already remote place where you’d find the nearest store or supply shop, ice source, shoreside processor, or shipping facility. The Alitak processing plant and fleet hub was the only viable place on the Island’s southern area to over-winter gear and vessels, and our primary source of fuel, supplies or mechanical support. It’s where we’ve sent essential cargo at the start of each season, the equipment, food and other goods we need to run isolated field camps for three months. Moving fish to market is a carefully orchestrated network of supply and services. All of that went away with the buyer, too.

It makes sense — they’re not taking our salmon, so they’re not going to provide us services. But this has many of us thinking about the scale at which harvesters, and remote communities, rely upon the large and increasingly consolidated private companies that make up the vast majority of Alaska’s seafood processing.

Many of the 40 setnet fishing businesses affected by the Alitak decision are family operations with a multi-generational history in the fishery. The Alutiiq community of Akhiok, established thousands of years ago, is also located just a few miles north of the processor’s facility. It’s one of six remote villages on Kodiak Island. While facility ownership has changed hands across the last 130 years, village residents, including local commercial and subsistence fishermen, have always been able to purchase fuel, groceries and other goods along with selling commercially caught fish. OBI is working with the Akhiok community and tribal leaders to problem solve the most critical services. And while other opportunities are being investigated for selling fish, it still feels like a long shot. Not too long ago, though, there was more than one buyer that regularly showed up in the area to purchase fish. Consolidations have affected that.

OBI was born just 4 years ago, after a merger of two well established Alaska processors, Ocean Beauty and Icicle. The re-branded OBI is now primarily owned by Cooke, and the Bristol Bay Economic Development Corporation, two massive players on the seafood scene. Cooke is the single largest private seafood company on the planet, and bought several other large seafood companies in the U.S. and abroad in the last year. That included Slade Gorton, one of America’s largest importer-distributors. And so Cooke’s growth continues. But, their subsidiary’s Alitak operation hasn’t turned a profit lately, and OBI stopped processing on-site in Alitak during Covid, shortly after the merger allowed them to consolidate Kodiak processing assets. The statewide salmon market outlook is poor, and Alitak’s harvest forecast isn’t breaking any records this year.

So what’s a multi-national corporation to do when they’re also seeing fiscal stressors in other Alaska regions, across salmon, pollock, crab, cod and sablefish? They cut the operations that no longer make sense for their margins and, unlike their larger industry investments, don’t project enough future profit to subsidize through a downturn.

That may be a fairly simple equation for a corporate business model, but for food systems generally and the 40 small fishing businesses who lost market access specifically, it’s a reality check on how we plan for the future. While large-scale harvest operations are an important economic and food-providing engine, small-scale operations collectively make up a massive part of Alaskan, American and global access to seafood. These upsets highlight the vulnerabilities of both processors and harvesters, and urge us to examine and address the risks of market consolidation, crumbling or moth-balled infrastructure, and the dependence on over extended private companies for that critical infrastructure and the food systems built around them. Small boat fishermen, their families, communities, and everyone their harvests feed, are relying on a shrinking number of companies that ultimately have bigger fisheries to fry.

It seems like every few years there’s a company, or a few, that experience major market failures, and it always comes with downstream impacts. Alaskan crab harvesters are suing Peter Pan Seafoods for non-payment of delivered catch valued in the 6-figures. By the end of 2023 the bottom had fallen out of the sablefish market so badly that fishermen with full holds were getting turned away at the dock. Other small communities around the state are looking at processors already gone from or about to drop out of critical cod and salmon markets, leaving harvesters with fish to catch but nowhere to take it.

It seems like every few years there’s a company, or a few, that experience major market failures, and it always comes with downstream impacts. Alaskan crab harvesters are suing Peter Pan Seafoods for non-payment of delivered catch valued in the 6-figures. By the end of 2023 the bottom had fallen out of the sablefish market so badly that fishermen with full holds were getting turned away at the dock. Other small communities around the state are looking at processors already gone from or about to drop out of critical cod and salmon markets, leaving harvesters with fish to catch but nowhere to take it.

While these are all just more symptoms of salmon and seafood markets in steep decline, and shouldn’t be attributed to any singular company, it should inspire fishermen to ask harder questions about how to rebuild and bolster resilience for harvester businesses across the U.S. The Alitak announcement came just days after the news that the USDA will be purchasing nearly $70 million in seafood inventory from OBI Seafoods alone, along with large purchases from other seafood processors. Those purchases are helping to move processor inventory at a time when the seafood industry is struggling with both market prices and access to sufficient cold storage. So like many other fishermen I advocated for, and still support, USDA purchases of American seafood as both a tool for American nutrition and a way to bolster this critical food system. I also understand that those buys, big as they may be, didn’t solve the problems of the Alaska processing sector, or their impacts on fishermen.

I also know that we need more and better disaster planning for harvester businesses, as much as our supply chain partners upstream. Because if Alitak’s small-scale harvesters can’t find another buyer, there isn’t a disaster relief program that can keep some of my neighbors from losing their sites. And no government support to processors ensures anyone a market, and it’s not meant to. So along with finding a fix for this season, we also need to identify what it is that the U.S. harvesting sector needs, as a global food provider and mainstay of coastal communities, in order to weather disaster, retain critical expertise and operations, and build resilience. We need diversified markets at varied scales, and rural community infrastructure that can support commerce, but isn’t entirely dependent upon or entitled to private companies. And we need functional, timely disaster relief for seafood harvesters.

It’s important to remember, too, that the long-term consequences in these situations are often not solely economic. They have implications for community well being and conservation too. If no market opportunity emerges, there will be additional concerns about how to manage the harvestable surplus of salmon headed to Alitak District river systems. Without an active setnet fleet fishing at typical effort levels, foregone harvest could lead to over-escaping salmon systems, which puts additional biological pressure on lake and river habitats and has the potential to exacerbate fluctuations in returning biomass. Even with additional or increased seine harvest, which also assumes there will be processors willing to buy it, it’s unclear whether the Alaska Department of Fish and Game would be able to manage harvest in a way that prevents over-escapement. Other potential impacts include the abrupt loss of biologic sampling done throughout the season in the Alitak area setnet fisheries, which could affect brood tables and other critical elements of fishery monitoring and forecasting conducted by state managers.

While harvesters are hopeful that they will piece together a temporary solution by summer, the potential for impacts to businesses, communities and management are significant. Alitak fishermen have asked several processors if they could work together on a cooperative, interim plan rather than face a full shut down. OBI has stated that they will consider purchasing Alitak setnet fish, but only if the small-boat setnet fleet is able to contract its own tender vessel services to transport the fish the 120 nautical miles to town, find their own ice source, and meet a list of requirements that are still being drafted.

I love the Alaska seafood industry, and I love being a fisherman. We have built incredible systems here, but like every human endeavor they are imperfect. Since I want to be a fisherman for the next 30 years, and want the opportunity to raise another generation of Alaskan fishermen, I find myself asking — is this seafood engine we’ve built one that we try to keep running as is? And we just try to keep up? Or do we need to adapt it one product line, one fishery, at a time, to be something more resilient, adaptable and accessible than the previous century’s model.